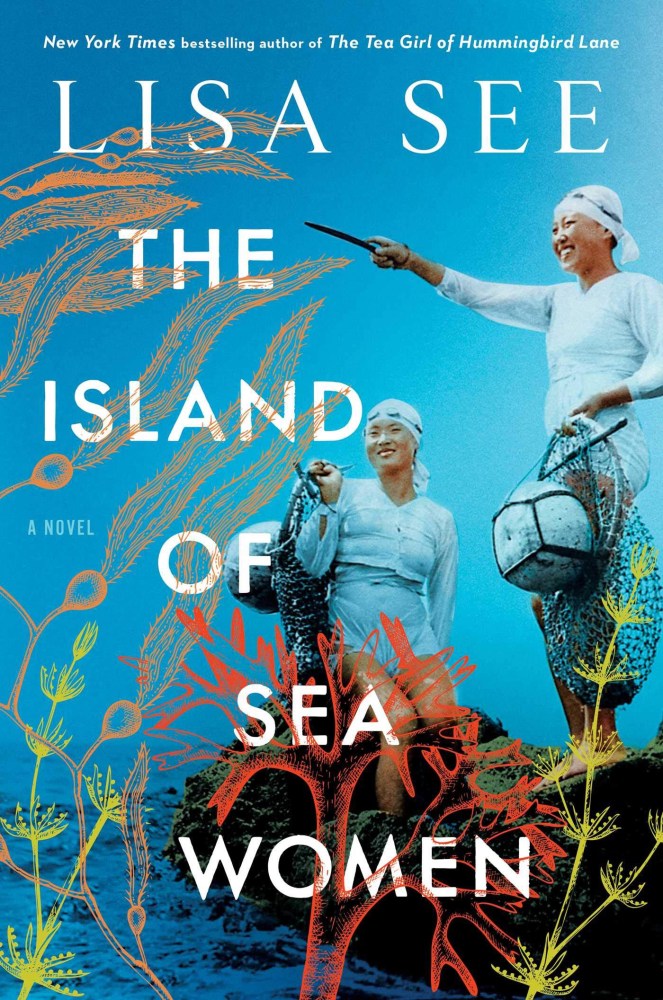

Sometimes, you should judge a book by its cover. This was my favorite book of 2019, and I based my purchase almost entirely on the interesting cover with two old ladies. As I brought the book home, it was a serious underdog, being beat out book after book with others I’d bought and borrowed. Finally, I picked this up last week after buying it at the Tattered Cover Bookstore on vacation in Denver in May. I was not disappointed.

Sometimes, you should judge a book by its cover. This was my favorite book of 2019, and I based my purchase almost entirely on the interesting cover with two old ladies. As I brought the book home, it was a serious underdog, being beat out book after book with others I’d bought and borrowed. Finally, I picked this up last week after buying it at the Tattered Cover Bookstore on vacation in Denver in May. I was not disappointed.

The number of Asian-American coming-of-age books the New York State curriculum force-fed me and my peers in middle and high school (I’m looking at you Joy Luck Club and Memoirs of a Geisha) has conditioned me to avoid Asian literature. I never enjoyed anything that we were told to read. It wasn’t relatable to me and I wrote it off. With the recent resurgence of all different types of multi-cultural fiction, I’ve been trying to diversify the stories I read to incorporate some stuff that might not be the most relatable for me, but is still very worthwhile.

The Island of Sea Women spans pre- World War II and wartime Korea, detailing Korean occupation by the Japanese and by the Allies. Japanese occupation of Korea began in 1910. This story begins with a distinct air of unrest with the Japanese- although there isn’t outright war, the Korean natives stay as far from Japanese insurgents and soldiers as they can.

The body of the story follows two female friends and their journey through life as haenyeo. Haenyeo are female divers who reside on the Korean island of Jeju, where a family living is made primarily by the female mother, who dives into the sea to collect food (primarily seaweed, clams and abalone, but sometimes octopus and larger finds) and other sea life to sell for income. The haenyeo collective is a matriarchal society, one that stands juxtaposed to the male dominated societies of the West, particularly in the 1940s.

First and foremost, I am grateful for having read this book because of what it taught me about Korean history. My grandfather was in the Korean War and I am ashamed to admit I knew close to nothing about the United States’ role in the emancipation of South Korea from Japan and North Korea, never mind anything about Korea itself.

Even better, the story of female friendship between Young-sook and Mi-ja. Mi-ja’s family were Japanese “collaborators” – a term thrown around pretty loosely. Her father worked in a Japanese factory on the Korean mainland. Orphaned at a young age after moving to the island of Jeju with her father, Mi-ja is taken under the wing of Young-sook’s mother, who is the chief of the village diving collective. She teachers the young girls to dive as haenyeo, to provide for their families as true Island women do.

Young-sook and Mi-ja’s lives deviate amidst a backdrop of world war. Mi-ja is arranged to marry a man from a Japanese collaborating family. Her similarities to Young-sook dwindle and Young-sook finds it harder and harder to maintain her sisterhood with Mi-ja.

War strikes the island, bringing tragedy to Young-sook’s family. Her losses are symbolic to her of Mi-ja’s insistence on not helping Young-sook’s family in their time of need. Surely her husband’s political ties could save them all? Her relationship with Mi-ja is never the same.

Haenyeo are known for fortitude, determination and strong will. Young-sook embodies these without apology. It is seen as a benefit for haenyeo to be this way, to endure in the face of adversity, but I think this contributes to Young-sook’s loss of oversight and her inability (or direct negligence) to sympathize with her friend.

There are secrets between Mi-ja and Young-sook that enable them to never understand each other. There is death between them before they can heal their wounds. If Young-sook has been willing and able to embrace her friend in her own lowest time with sympathy rather than judgement, she would have come to easier realizations. Instead she harbors resentments, using her strength of character to put up an impenetrable wall against her friend.

The things lost between them are devastating. In a time when there is infinite loss and terror, two friends are driven further into turmoil, against each other, following societal lines of demarcation.

Lisa See’s novel details the lives of strong, immovable women, women I found to be extremely worthy, laudable, and noble. She highlights, however, how even the most noble can be flawed and can be inhibited from making the best choices as humans, even if they believe they are following an understanding of what’s right.

See’s writing is so enjoyable- like a refreshing dip in the ocean. May we learn from the haenyeo and from these characters something about grit, perseverance, and empathy.

There has been a lot of hype around The Handmaid’s Tale lately, particularly in the relativity of this story to modern society and female rights.

There has been a lot of hype around The Handmaid’s Tale lately, particularly in the relativity of this story to modern society and female rights. Oops, I did it again. I got overly excited about a book with rave reviews, a book that’s absolutely blowing up online and on social media, and I got a little let down.

Oops, I did it again. I got overly excited about a book with rave reviews, a book that’s absolutely blowing up online and on social media, and I got a little let down.