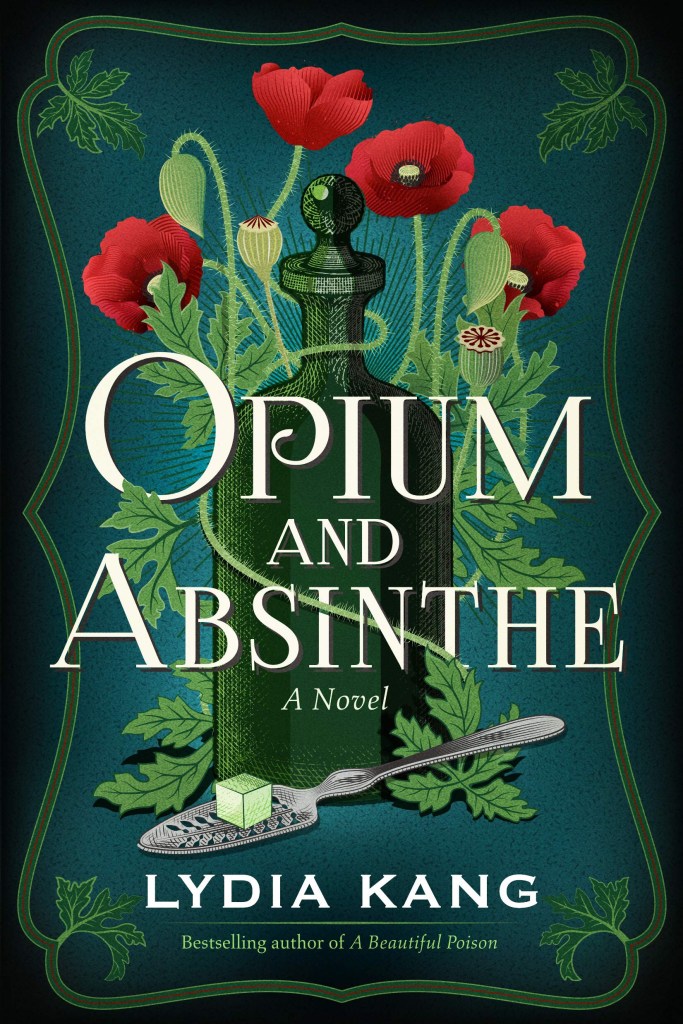

When you think about New York City at the turn of the century, 1899 going on 1900, what do you think of? In the past I might have said Industrialization, immigration and tenement living. All of these play a role in Lydia Kang’s Opium and Absinthe, but the story covers so much more. From the Upper West Side to the Lower East, from the Astors to the Newsies, this story explores the inner workings of NYC and a young well-to-do girl who navigates them in order to solve the mystery of her sister’s death.

Tillie Pembroke is a teenage girl with a fondness for reading. She loves to learn and consistently consults her Dictionary, a steady companion. Tillie suffers a horse riding accident, breaking her collarbone. When she wakes, she gets the news that her sister is missing, and later finds she’s been murdered. Lucy is found with small bite marks on her neck, her body devoid of blood. In her despair, Tillie turns to the medicines that her doctor has prescribed for her pain – laudanum, opium, morphine, and then heroin. Each that is provided to her is easier to secure than the last. They are given easily as an outlet for her pain, as a sedative, to prevent “hysteria” as is so common with emotional women. Most importantly, they are given to silence her, to stop her asking questions, to demure her inquisitive nature.

The story is told through Tillie’s perspective, and through most of it, Tillie is addicted to painkillers. I thought this was an intriguing POV. As Tillie comes to realizations about her wellness, her sister’s death, her relationships, the reader learns them through the clouded lens of Tillie’s drug use. The reader sympathizes with Tillie’s need for opium to dull the pain towards the beginning, but panics about her subsequent addiction. It was a perfect way to make sure the reader empathized with Tillie and was invested in her recovery.

This part of the novel was an important commentary on mental health, which Lydia Kang actually mentions in her writer’s notes. Although the prescriptive qualities of these drugs were permissible at the time, the overwhelming addictive qualities were ignored. Tillie is checked into a rehab facility, but is quickly given heroin pills by a suitor in an effort to win her affections. Tillie is eventually able to possess the mental stamina to withdraw herself from the drugs, her need for the truth about her sister driving her desire to be sober.

Once lucid, Tillie dives into her leads, investigating with the help of a Newsie turned-journalist, Ian Metzger. Ian is a parentless teen who shows Tillie the underbelly of the city, sparking her interest in journalism further.

I really enjoyed this book. Paralleled by Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which had just been released at the time, Tillie is enthralled by vampire lore, trying to tie the threads of her sister’s death together to identify a killer. Quotes from Dracula open each chapter, setting the stage for the macabre mystery. In the end, however, Tillie finds that a much more human foe is the culprit.